The Diag

The Separation of Church and State (streets)

The University of Michigan’s central campus sports a walkway that cuts from its northwest corner down to its southeast. To students today, this walkway is lovingly known as “The Diag”. It is a quick way to cut across campus, and there are numerous little walkways that sprout out from its main walkway, allowing students to freely travel from building to building on central campus. This use of space makes total sense to us in the 21st century. We’re expected to do everything quickly in this day and age, and the Diag accommodates for that, making it easy to walk distances that would be cumbersome to traverse had they lacked pavement.

It is interesting to consider, then, the Diag before pavement. Indeed, as we’ll get into, the Diag used to be completely unpaved, because there was no “Diag”. The University of Michigan central campus was merely a few buildings and a natural space when it moved to Ann Arbor, a yeoman ideal that Jefferson would be proud of. What does the appearance and subsequent renovations of the Diag say about the history of the University of Michigan? Furthermore, what does it say about the history of America? To try to answer these questions, I looked at numerous maps of U of M’s central campus. These maps were found online at the Ann Arbor Historic Maps Project (part of the U of M Millennium Project) and at the Bentley Historical Library on the University of Michigan’s North Campus.

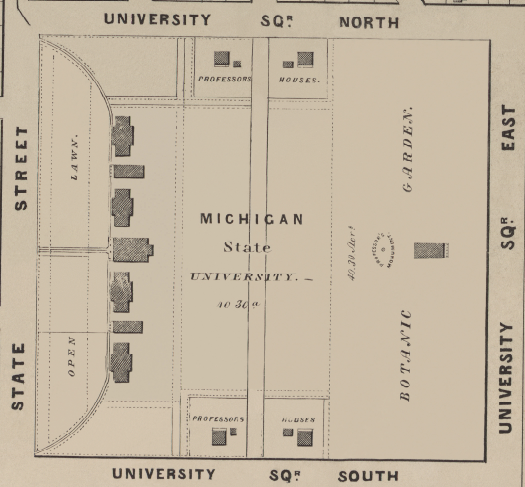

Campus in 1854. No sign of the Diag; the focus isn’t on transportation yet.

The first map I want to draw attention to is this one, drawn from the Ann Arbor, Michigan Historic Maps project. This is the University of Michigan campus in 1854. As you can see, there is no “Diag” to speak of; the University is striving for a pastoral ideal. There appear to be some paths that are mostly for the benefit of professors, as they connect their houses to each other and the main University building. The building in the middle of the “Botanical Gardens” area is the old Medicine Building. It’s interesting to see just how far the University has come in this field; in 1854, there wasn’t even a path to this building, and now the campus sports a famously large hospital and medical campus. This map is a good place to start; there isn’t much there, but what is present forms the backbone of the future central campus.

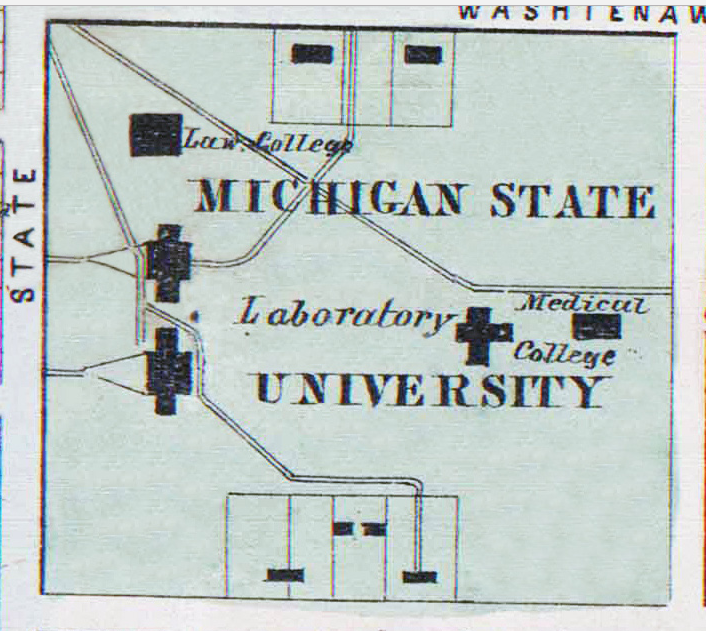

The Diag, in 1864, began to expand and take on its diagonal shape.

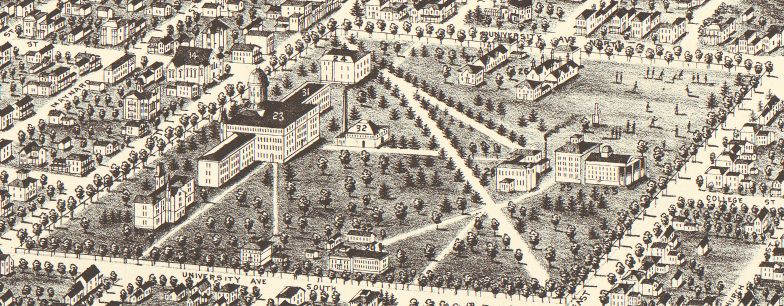

A rendering of what the Diag looked like in 1866. A pastoral, peaceful place.

These next maps are from the Historic Maps Project as well; the rightmost being 10 years later than the first, the left one being 1864, and the rightmost from 1866. There aren’t any discernible campus layout differences between them, but the 1866 map is useful for visualizing the campus around this time, a pastoral area. The 1864 map can be contrasted with the 1854 map in striking ways. There is more of a focus on the Medical Campus now; and indeed, we see the first markings of the modern Diag. It comes down from the northwest, going straight for the Medical College. So then, the Diag began as a way to quickly get to the Medical College, heretofore a bit of an isolated area.

The idea that students should be able to traverse a large space quickly seems a focus of this construction from the very start. If you look at the 1866 map, you can see that the pastoral still plays a large role in the school’s self image; the Diag, and furthermore the whole campus, is lined with neat, apparently equidistant rows of trees. This is roughly antebellum America; not quite the industrial powerhouse it would become by century’s end. This shows that the Diag progressed as the world around it did; its expansions and new pathways are emblematic of an expanding country.

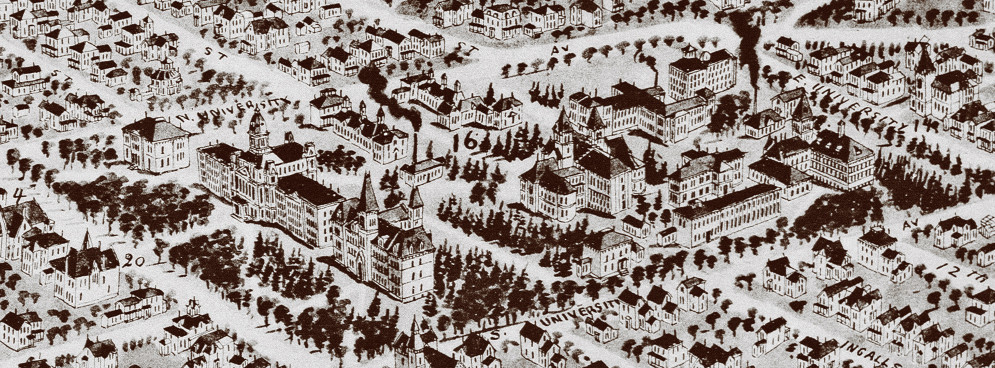

In 1880, the Diag still retained that pastoralism, but this map adds a social aspect with bodies playing in the northeast.

Many more buildings are present in the 1890 map. The smokestack gives this image a more industrial appearance.

The period after the Civil War was a time of great expansion for the university. As this map on the left shows, by 1880 the Diag completed its journey from northwest to southeast. While trees and the pastoral still play a large part in the image of this map, there are also more buildings, and ones that existed before are grander. It’s beginning to closely resemble our modern day central campus. This map also gives more character to the campus area, as later maps sometimes did. There are people playing games in the northeast corner of the Diag, in what is an open field (and what will become a gymnasium soon). The map on the right isn’t as useful for seeing a layout of the Diag, but there is a striking feature about it; the appearance of smokestacks. These large smokestacks are no longer there, but in this moment, they represent the industrial ambitions of turn of the century America.

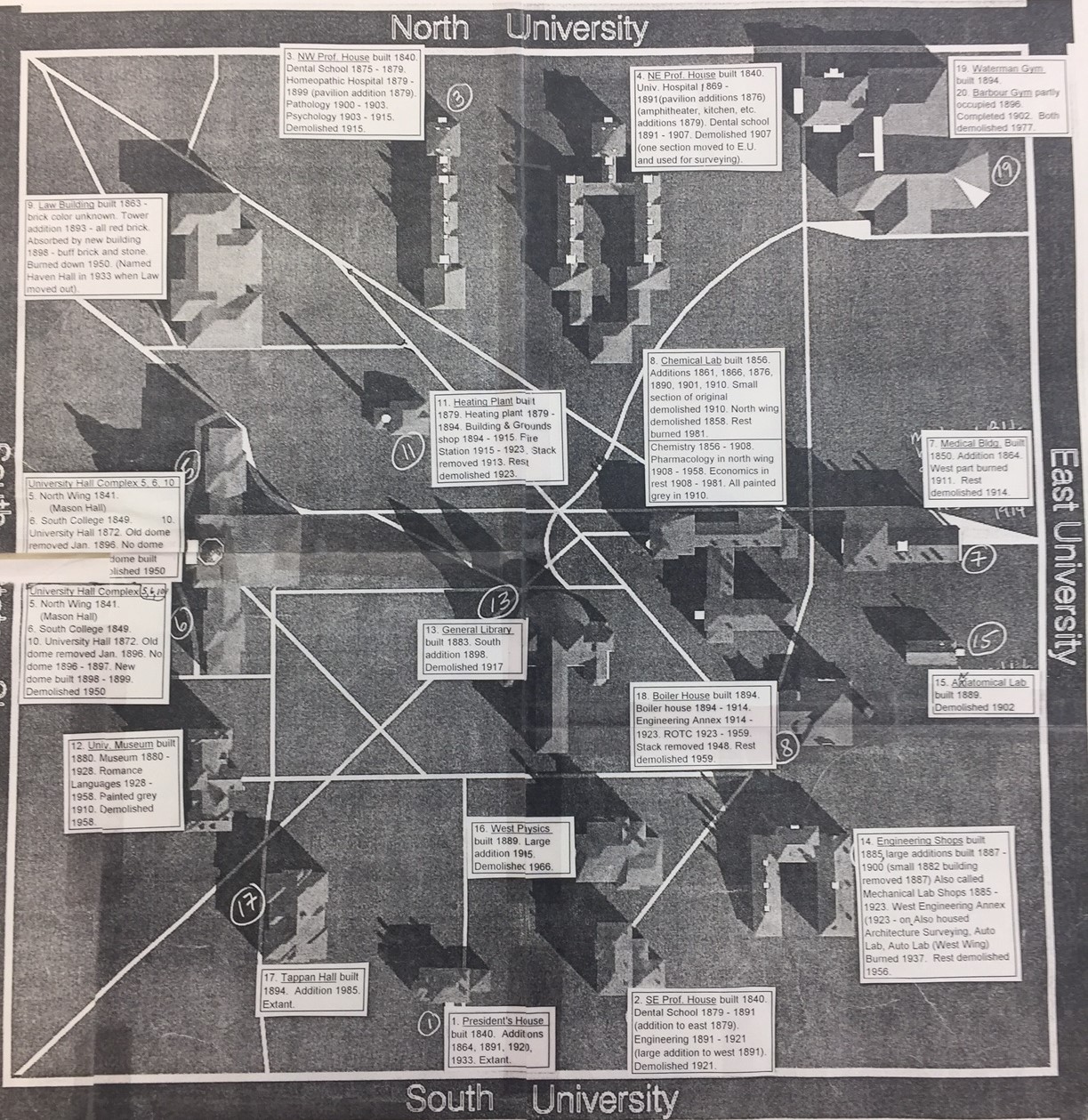

This map approximates what campus looked like in 1900. Made in 2001, its captions are useful for seeing when buildings disappeared.

Those smokestacks belonged to the Heating Plant and the Boiler House, buildings that are since long gone. This map approximates what the Diag looked like in the year 1900. This above map is a useful resource for picturing how the main University must have looked from the turn of the century to the post-World War I years. In addition to the now extinct smokestack buildings, there is the presence of the Waterman Gymnasium in the same spot where the Chemistry Building resides today. Central campus, in the year 1900, was starting to assume the centrality inherent in its name. It was not only a place where students could study, but also a place of recreation and fitness, at least while Waterman was still there.

The Diag is a living artifact, one that changes with the times much like anything else. In this sense, it is more than just a glorified sidewalk; the Diag may be talked about like any building that resides near it. It is added on to, like new buildings that appear as the University needs them, and segments are also destroyed to make way for the new. Consider how the Heating Plant and Boiler House are now gone; as technology improves, the University decides what happens to the old.

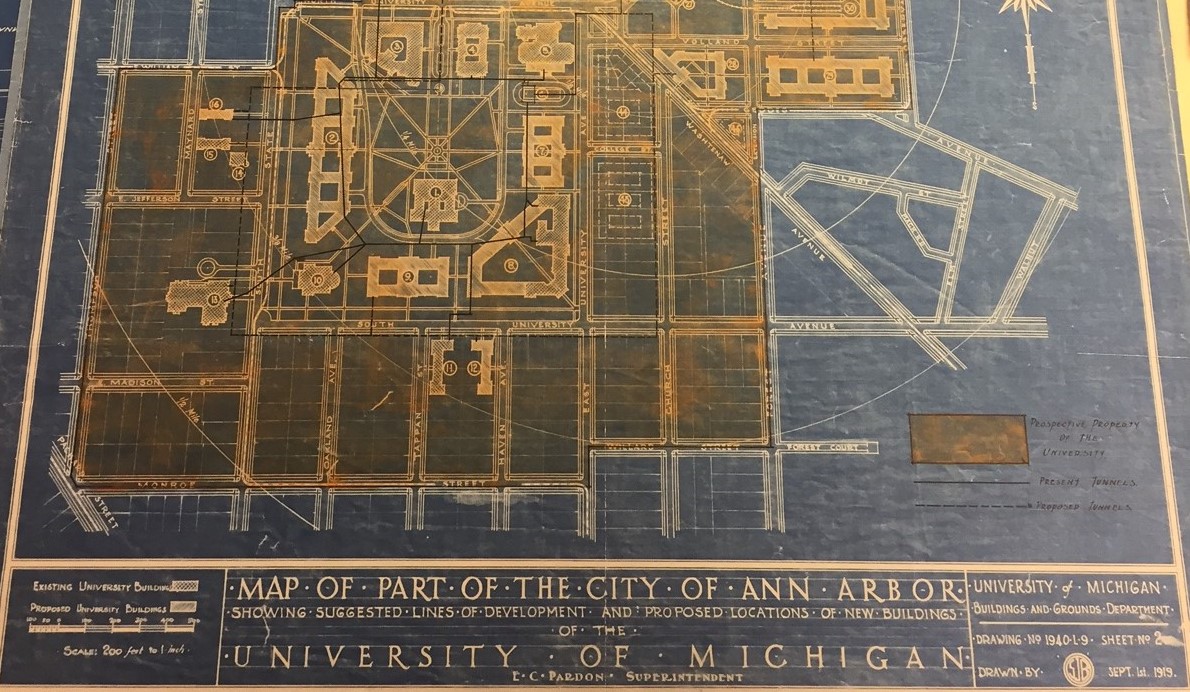

The campus, real and proposed, in 1919. The Diag is taking on more pathways to go to more buildings.

After World War I, the University underwent a period of expansion, and this map from 1919 illustrates well the scope that the University was envisioning. The area in yellow, which envelops more than just the original campus, is the “prospective property of the University”. The University was thinking expansionist; some buildings on the map are outlines of future buildings. This map is a blueprint of the future U of M campus, and a portent of things to come; a sprawling campus with numerous buildings that are on main campus and also, eventually, integrated into Ann Arbor itself.

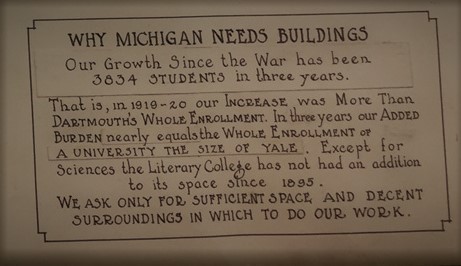

Michigan needed buildings post-WWI to deal with an increase in the student body.

The Diag itself on this map is quite sprawling as well. Compared to the 19th century version, there are many more pathways, and many more ways to travel, well, diagonally. With the addition of new buildings, it becomes necessary to be able to traverse them quickly. There was also the issue of student body; after WWI, the student body of U of M also underwent a large expansion. More students means a need for more room, which is reflected in this plan for the Diag.

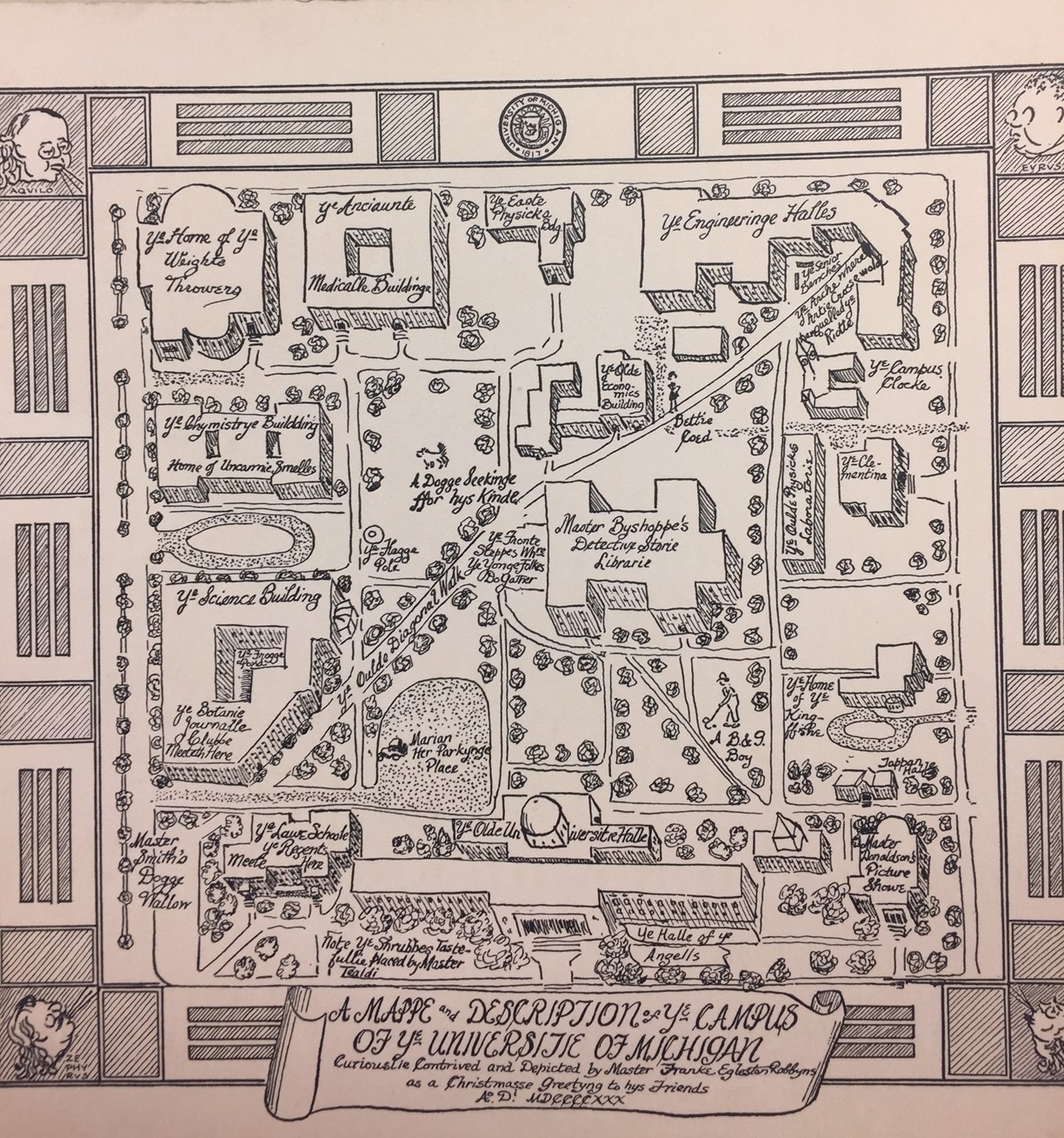

This amusing map from 1930 is representative of the Diag as a social space. It has been blown up so the old-timey text may be better read.

One aspect of the Diag that has not been discussed is the social aspect. The Diag, due to centrality and wide use on campus, is a place where many students come together daily, and that was true in 1930 as it is today. This map was a delightful find in the Bentley; hand drawn by Frank Egleston Robbins, an assisstant to the University President in 1930, as a gift to friends. This is a truly informal map, and reveals what social uses and lore were associated with the Diag almost 100 years ago. It is striking to see the parallels between then and now. For one, the Diag is called, jokingly (as all the definitions on this map are), “ye olde diagonal walk”.

The man who drew up the fancy 1930 map. Even assisstants to the president can have a little fun.

One can get lost in the many features of the map that suggest old inside jokes. Just why are the benches near the Engineering Arch the “senior benches?” The map is emblematic of the feeling of learning about college lingo, a feeling that persists today among freshmen everywhere. In the grassy area, there is a “dog seeking for his kind”, which suggests the Diag was a popular dog-walking spot. It certainly is that today!

As the veins and arteries of central campus, the Diag is an area that many students use and depend on to traverse campus, and it is also a place where people come together to experience the University of Michigan. Using maps as evidence, one can trace how it came to be this way; as history went on, and as the United States at large expanded, so did the campus, and thus the Diag. Today the Diag remains a symbol of what it always has been; a way of progress for all people, and a public good concerned with efficiency and expansion.

The Diag, seen from the steps of Hatcher Grauate Library, April 27th, 2017.

Image Credits

-

Title card image: “Campus Beauty” - restroom on diag, fenced (near oldest hospital wings), Sam Sturgis photograph collection, Bentley Historical Library. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhl/x-hs11606/hs11606

-

Maps from 1854, 1864, 1866, 1880, and 1890: “Ann Arbor, Michigan Historic Maps Project”, Millenium Project, University of Michigan, 2011. http://um2017.org/2017_Website/AA_MAPS.html

-

1900 map: “The University of Michigan Diag, circa 1900”, University of Michigan Plant Extension Services, 2001. Bentley Historical Library

-

1919 map and map key: University of Michigan Building and Grounds Dept.”Map of part of the city of Ann Arbor: showing suggested lines of development and proposed locations of new buildings of the University of Michigan.”, 1919. Bentley Historical Library

-

“Why michigan needs buildings”: University of Michigan. “At one glance the University of Michigan and its needs”, 1922. Bentley Historical Library

-

Frank Egleston Robbins paper: University of Michigan. “At a glance, the needs of the University of Michigan: prepared to inform the legislature of 1923”, 1923. Bentley Historical Library

-

Ye olde 1930 mappe: Egleston, Frank Robbins. “A mappe and description of ye campus of ye University of Michigan”, 1930. Bentley Historical Library

-

Diag 2017: Author’s own photo