Buying Schools to Make Schools

As Don Callard of The Ann Arbor Observer wrote, ‘nothing expands like a university,’ (Callard 2009). Learn how the University of Michigan covered ground for its expanding needs through the acquisition of public schools.

As early as the 1880s, the University of Michigan was beginning to realize that they were running out of space to house their growing needs. Everything from student housing, research laboratories and classroom halls needed to be somewhere, and the current acreage owned would not be able to cut it for much longer. The following essay tracks the University’s involvement and ownership in two public schools in Ann Arbor: Tappan School and Ann Arbor City High School. The University also purchased a third public school, the Perry School in 1967.

Tappan School to East Hall

In 1883, the Ann Arbor School Board allocated $10,988 to build Tappan School on East University Avenue near Church Street (Berry 1954, 1). Today, many Ann-Arborites may recognize this location as present day East Hall, home of the University’s departments of Mathematics and Psychology, and they would be right. While today East Hall is a formidable presence on the eastern side of the Central Campus Diag, the University’s acquisition of this space was met with much chagrin.

In fact, though Tappan School was built not forty years before, by 1920, it was recognized that the school was inadequate: characterized by overcrowdedness, not forward thinking curriculum wise (as many parts of the country embraced the junior high school model with ‘progressive education’) and had facilities that had fallen into disrepair (Berry 1954, 4). Local fire inspector reports from the time corroborate that the school did not pass the fire codes and was unsafe.

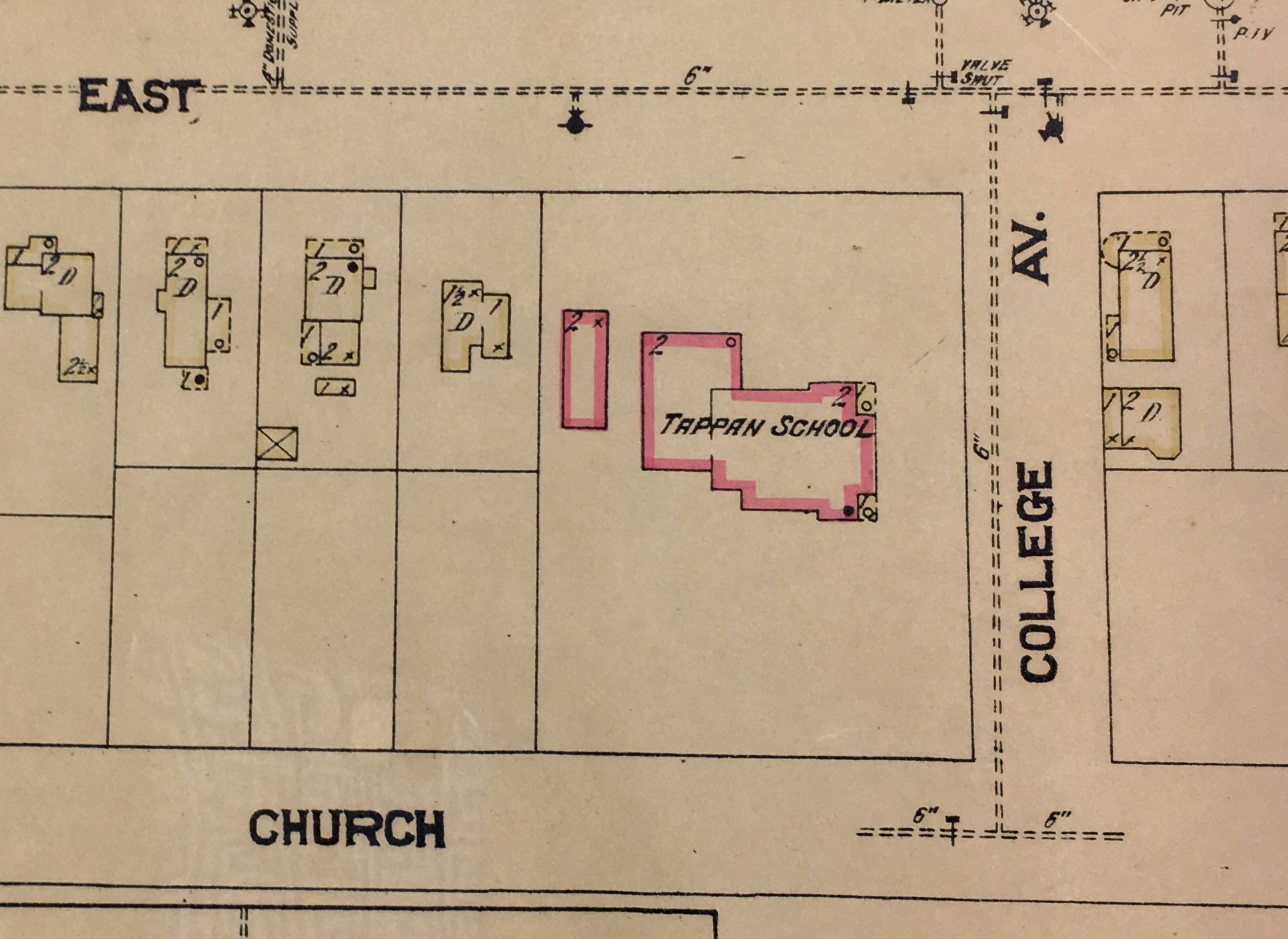

A 1917 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map showing Tappan School, outlined in pink to indicate its inadequate infrastructure.

Additionally, administrators noted that Tappan School was “badly located with reference to its district [students who lived in a particular part of the city of Ann Arbor] being directly across the street from the University campus on land which the University will undoubtedly acquire in time,” (Berry 1954, 4). By 1921, the Ann Arbor School Board had plans to shut it down and build a new school on a location purchased on South University Avenue that was more centrally located for the students in the district (Berry 1954, 4).

In 1923, the prediction came true: the University of Michigan purchased Tappan School on East University for a sum of $76, 211, intended to be “turned over to the Engineering College for its over-flowing class” (Berry 1954, 7). Following this acquisition, confusion ensued for the Ann Arbor School Board over naming rights. The School Board faced a decision: they believed that the University would retain the name Tappan School for the building they had just purchased as a way to honor the University’s first president, Henry Phillip Tappan. Thus, the School Board struggled with how to name the new school on South University. The possibility of naming it after revered University president James B. Angell School was offered (Berry 1954, 7). However, this headache resolved itself partially when “it became evident that the University was to re-name the old building East Hall,” (Berry 1954, 8). As a result, the School Board named the new school “Tappan Junior High School”, a reflection of the school system’s recognition of teaching philosophy of the junior high school model and as a way to accommodate prior over-enrollment (Berry 1954, 8).

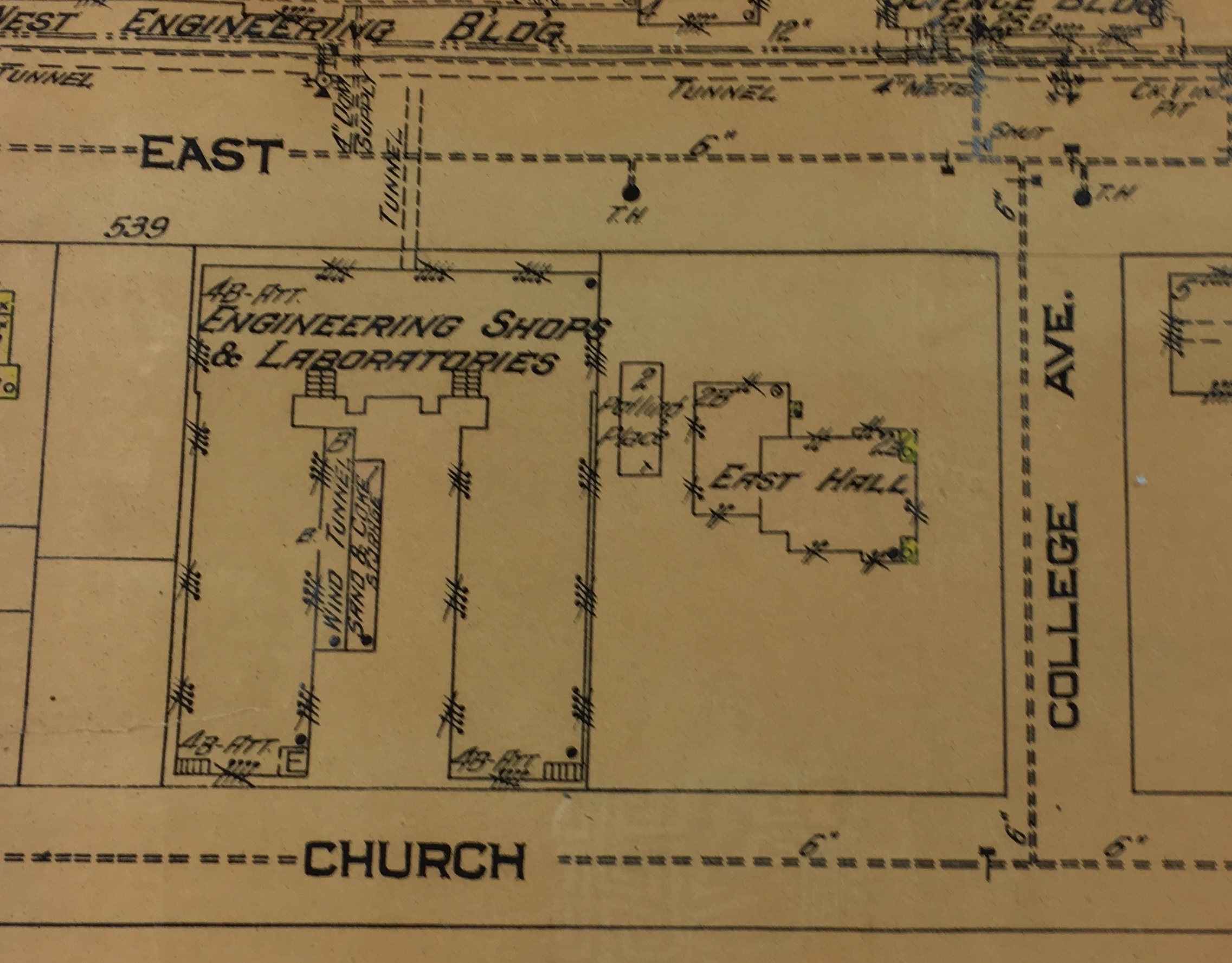

A 1938 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map demonstrates the building’s change of name and updated infrastructure with a yellow outlined portion.

Union to City to Frieze to North Quad

On the other side of the Diag lies the present-day site of North Quad, a living and learning community, dining and academic complex. From State Street and Washington Street, this tall red brick structure looks impressive as it enters its seventh year of existence. However, if one goes on Huron Street and looks at the back of the façade, this will see something that does not quite resemble the rest of the architecture: the original columned entrance to the Carnegie Library of Ann Arbor.

The façade of the Carnegie Library today.

Before the Carnegie Library was built however, the site had much more history to spare. In 1839, four businessmen purchased the site, recognizing its potential in its proximity to the recently settled University (Mason 2005, 7). In 1855, the land was deeded to the Ann Arbor School District followed by the construction of a high school on the site called Union School in 1857 (Mason 2005, 7).

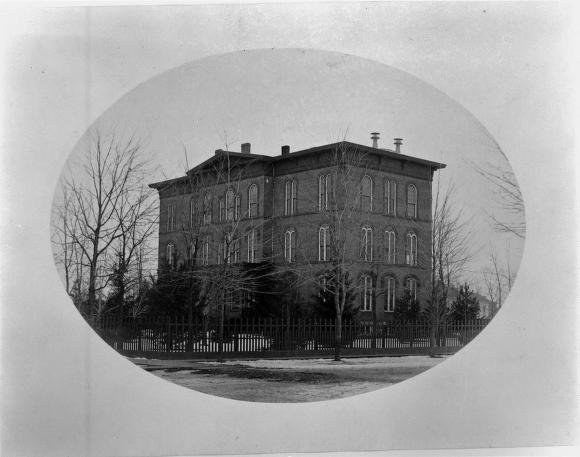

Union High School circa 1879.

As the story goes, in 1904, all of Union School was destroyed beyond repair by a fire in the middle of the night with the exception of the library’s contents, which was spared (Mason 2005, 11). Recognizing the need for a high school in the area, a new school was built—Ann Arbor City High School—with an attached library within. (Mason 2005, 16).

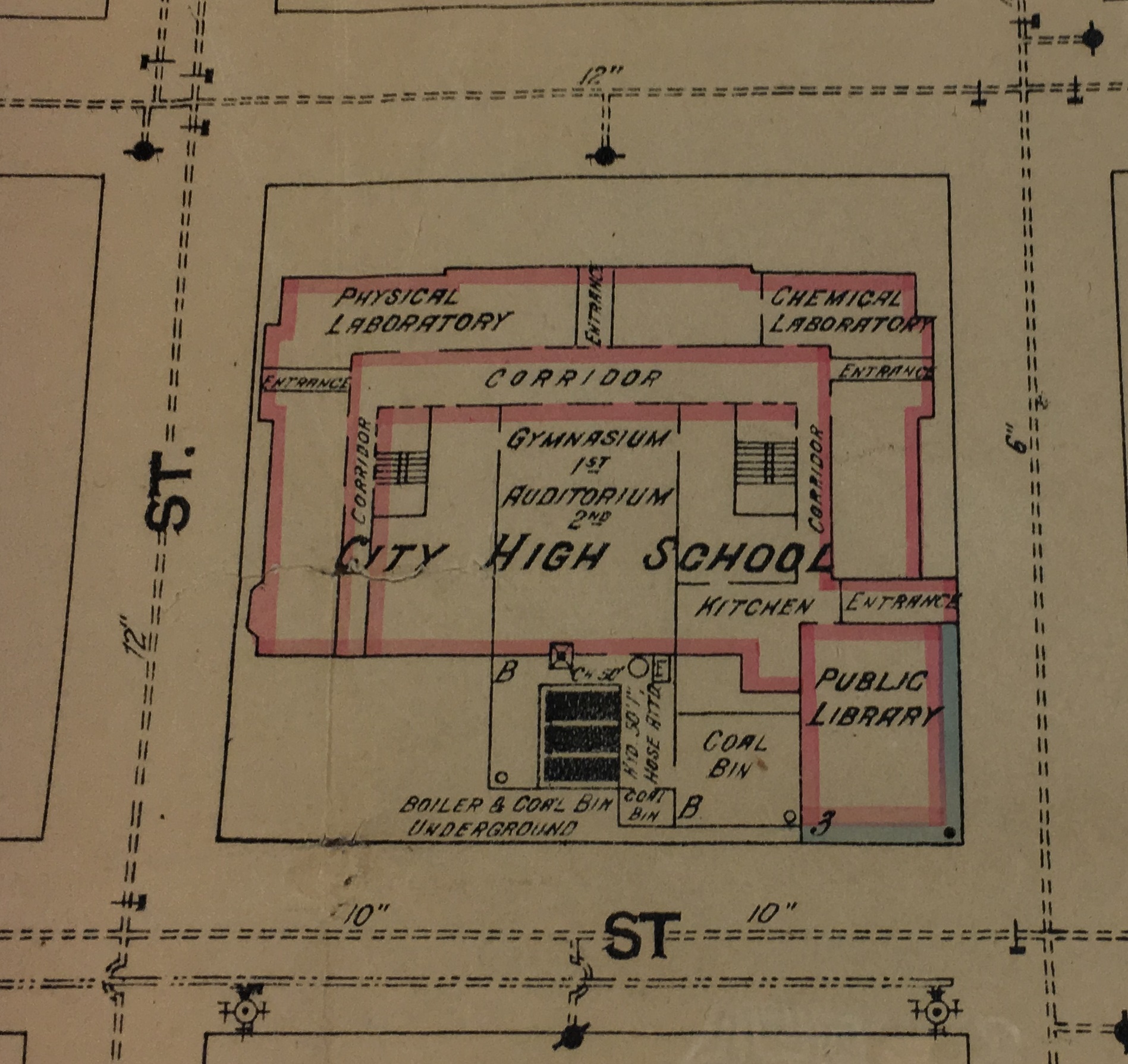

A 1938 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map shows City High School outlined in pink to indicate its inadequate infrastructure

Andrew Carnegie

Remarkably, this attached library to “City High School” as it was called was the only library for all residents of the city, serving more than solely the students. For many years, residents, including the Ladies Library Association, had been jockeying for a new library to exist beyond the school (Mason 2005, 9). Thus, the community found it to be optimal time to apply for a Carnegie Grant, an initiative supported by the business magnate Andrew Carnegie funds, which permitted the library and school to be built simultaneously (Shackman 2009). In 1924, supported by the realization that the school had fallen into disrepair, Ann Arbor residents began to rally around the idea of building a freestanding library, which did come to fruition in 1957 with a location on Fifth Avenue (Shackman 2009).

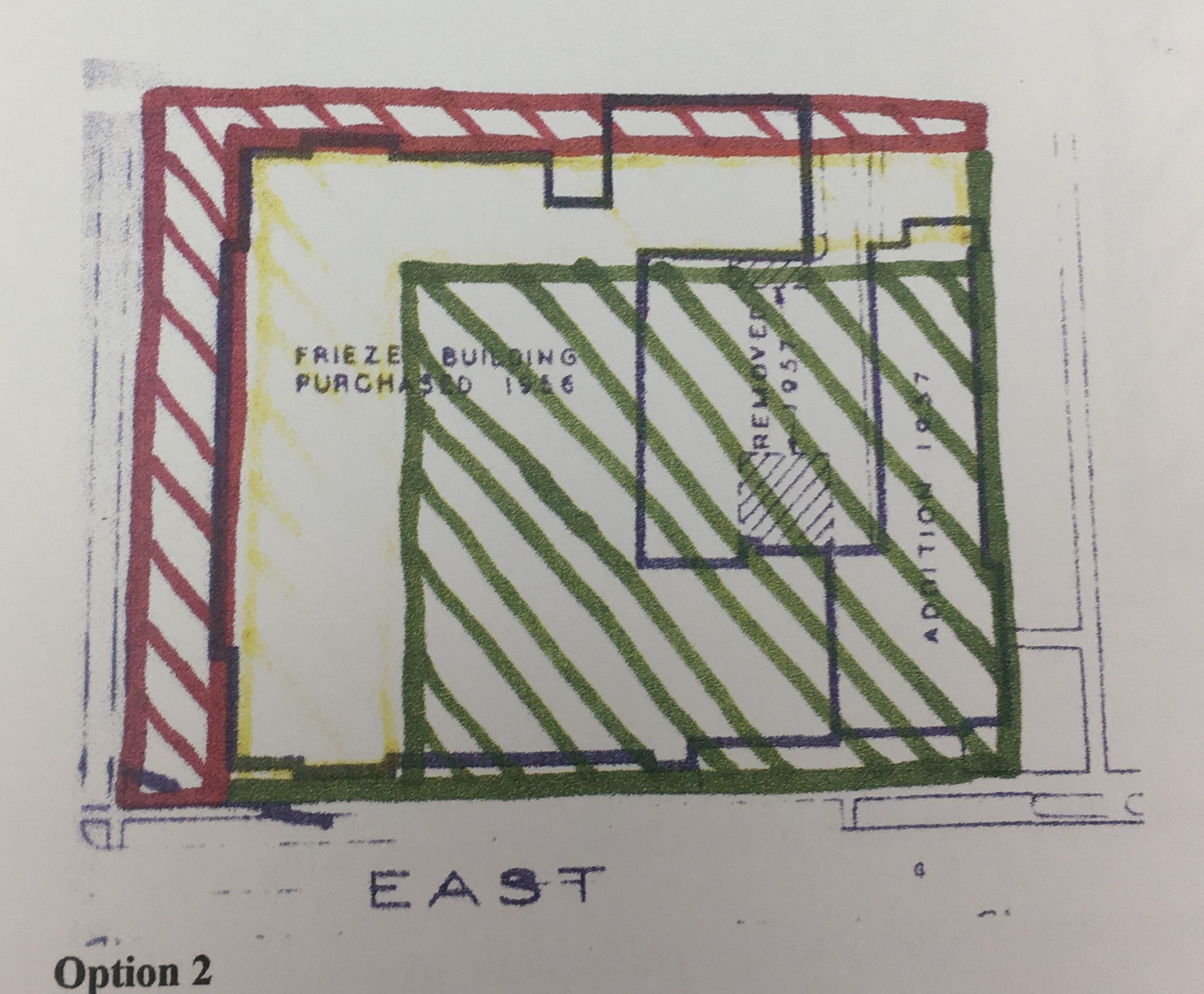

Meanwhile, City High School was falling into deeper and deeper disrepair. The Ann Arbor School Board decided to announce plans to shift enrollment of high school students to a new, recently constructed location near the southern end of the University’s campus, Pioneer High School (Mason 2005, 16; Pioneer Band Association records, 1912; “Catalogue of the Ann Arbor High School”). By 1956, much like what occurred with the acquisition of Tappan School years before, the University of Michigan purchased the City High School site for a sum of $1.4 million and renamed it the Frieze Building after former University President Henry S. Frieze (Shackman, 2009). Curiously, while many students today may not recognize the Frieze name and may attribute the name to an architectural feature (frieze as in sculptural decoration) he was a revered individual, educator and professional during his time ([Pamphlets and articles about Frieze], see eulogy and erection of monument remarks by presiding University President Angell).

Despite renovation efforts in 1957 to update the building, the Frieze Building was never a sound reflection of what a University building can be, resigned for years for its decrepit condition (Vosgerchian 2007). Still, the space was used to house academic departments such as Communication Studies and Theater for a time (Vosgerchian, 2007). In 2004 however, University President Mary Sue Coleman announced plans to tear down the building and construct North Quad (Mason 2005, 19) Many Ann Arborites and City High School alums expressed anger at the news, believing the site should be preserved and renovated due to the Carnegie Library and high school’s history (Mason 2005; Vosgerchian 2007). Eventually, a compromise was reached, which led to the incorporation of the façade of the Carnegie Library and various architectural elements of the original building (Mason 2005).

By studying the University’s acquisition of public schools, this trend of ‘buying schools to make schools’ shed light on one strategy to expand a footprint within built parameters.

One of the plans presented for the North Quad site.

Sources

- “Andrew Carnegie, Philanthropist” http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/carnegie/aa_carnegie_phil_1.html

- Ann Arbor Board of Education. Catalogue of the Ann Arbor High School for the academic year. 1895-1896.

- Berry, Margaret D. “A History of Tappan Junior High School.” 1954.

- Callard, Don. The Lost Street Names of Ann Arbor. The Ann Arbor Observer, July 24, 2009. http://aaobserver.aadl.org/aaobserver/19282

- Mason, Jeremiah. “The Frieze Building : an informal report analyzing its past, present, and future /”, 2005.

- “North Quadrangle.” Student Life at the University of Michigan. 2017. http://www.housing.umich.edu/undergrad/north-quadrangle

- [Pamphlets and articles about Frieze]. 1889-1899. Bentley Library envelope, call number J 13.12 A1

- Pioneer Band Association Records, 1912. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- Shackman, Grace. “Ann Arbor’s Carnegie Library.”, The Ann Arbor Observer 2009. http://aaobserver.aadl.org/aaobserver/15245

- Vosgerchian, Jessica. “The rise and fall of the Frieze building”, The Michigan Daily, February 9, 2007. https://www.michigandaily.com/content/rise-and-fall-frieze-building

Image credits

-

“A 1917 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map…” 1917, Ann Arbor Fire Department. The Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.

-

“A 1938 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map demonstrates…” 1938, Ann Arbor Fire Department. The Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.

-

“The façade of the Carnegie Library today” 2017, author’s personal photograph.

-

Double image: “Frieze Building (including Carnegie library building), corner of State and Huron Streets, February 1958; HS1812.” Bentley Image Bank. Bentley Historical Library. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhl/x-hs1812/HS1812?from=index;lasttype=boolean;lastview=thumbnail;med=1;resnum=7;size=20;sort=relevance;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=carnegie+library

-

“Union High School circa 1879.” ‘Union (Ann Arbor) High School 1856-1879; BL000932.’ Bentley Image Bank. Bentley Historical Library. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhl/x-bl000932/BL000932?from=index;lasttype=boolean;lastview=thumbnail;med=1;resnum=1;size=20;sort=relevance;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=union+high+school

-

“A 1938 Ann Arbor Fire Inspector’s Map shows City High School…” 1938, Ann Arbor Fire Department. The Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.

-

“Andrew Carnegie, Philanthropist” http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/carnegie/aa_carnegie_phil_1.html

-

“One of the plans presented…” Jeremiah Mason, 2005. “The Frieze Building : an informal report analyzing its past, present, and future /”, 2005.